As the sun rises each morning over the Humber Bridge, last night’s good times and office party drinks flow by the last city in England, as nearly 30% of England’s land area drains into the North Sea. In the morning after the day before, a 2019 joint study by the Universities of Hull and Leeds found high concentrations of prescription drugs in the water, which included painkillers such as ibuprofen and the antidepressant citalopram—a drug with 17 million users in England. This tonic for our times, used to treat social phobias, panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive and major depressive disorders, flows through the body politic and under the bridge.

To the east, contemporary Hull clings to the edge of the concrete-lined salt marshes of the estuary, where it defiantly claws onto the skyline against the odds. Tapped into the ground with pile foundations, most of the city sits on sinking land underneath the North Sea.

Hundreds of years since the Statute of Merton underlined the difference between them and us, majority existence has been defined by struggle and strife. Forced from common land ways of being, the few expelled the many from a thousand years of self-sufficiency. Dragged kicking and screaming from the community harvest feast, pulled backwards through the sharp hawthorn hedgerow claws of Inclosure Acts. Life uprooted from dawn chorus song, pushed into the grinding machinery roar of city wage slavery. Poet John Taylor captured the dread many felt when compelled to seek work in places like Hull: whipping stocks awaited the homeless, press-ganged into posh pirates’ Royal Navy wars, or for the unlucky/lucky escape, a drowning in the river.

There is a Proverb, and a Prayer withal, That we may not to three strange places fall: From Hull, from Halifax, from Hell, ’tis thus, From all these three, Good Lord deliver us.

Hull hasn’t always been skint. In the late 13th century, it became one of the wealthiest towns in England, a major exporter and importer of construction and shipbuilding materials. Up until the late 20th century, it was one of the world’s biggest seaports, landing bounty dragged in nets from Dogger Bank fishing grounds. At its peak in the 1950s Hull boomed: fish factories, shipwrights, riggers, net makers. As fish stocks dried up, freezer trawlers brought fish from further away. Three ‘Cod Wars’ with Iceland later, a 200-mile exclusion zone kept Hull’s ships out. During these good times, poet Philip Larkin described Here:

A cut-price crowd, urban yet simple, dwelling Where only salesmen and relations come Within a terminate and fishy-smelling Pastoral of ships up streets, the slave museum, Tattoo-shops, consulates, grim head-scarfed wives;

Alas, by April 2021 there was only one remaining firm still based in Hull, with a fleet of just one freezer trawler, the Kirkella. Before Brexit, this state-of-the-art vessel carried much of the UK’s cod and haddock from 1,500 miles away off the coast of Norway. Now, post-European Union deals have reduced the quantity of fish available to catch by 50%, and the future of this boat is in doubt. Whilst the winning Brexit referendum votes were being counted, hopes of a new golden age for UK fishing on the north-eastern coast were already failing as the UK government drew up plans to ban fishing on Dogger Bank to stop cod extinction in this habitat.

Even in these downtimes of ruined economy, the alchemy of making things in Britain means that poorer parts of the city smell of plastic, sulphur, diesel, and glue. Thirst from a hard shift in the factory is quenched by a tinny of beer cracked open on the bike ride home along “road”. Between sips, weaving through the lines of hard times etched onto the faces you pass. At Bus Stop Café, friendships hold everything together; in between the sips of tea and plumes of cigarette smoke, pals look out for one another and make the city work.

In East Hull especially, there is a solidarity you don’t see in many other places. Through sepia tones and difficult times, people make the best of things, past their sell-by date stock, stacked high and sold cheap, getting on with whatever is needed to keep yourself upbeat. Here in England’s biggest village, family is lived down the same streets, and disdain for Thatcher and her part in the poverty trap is passed intergenerationally via DNA.

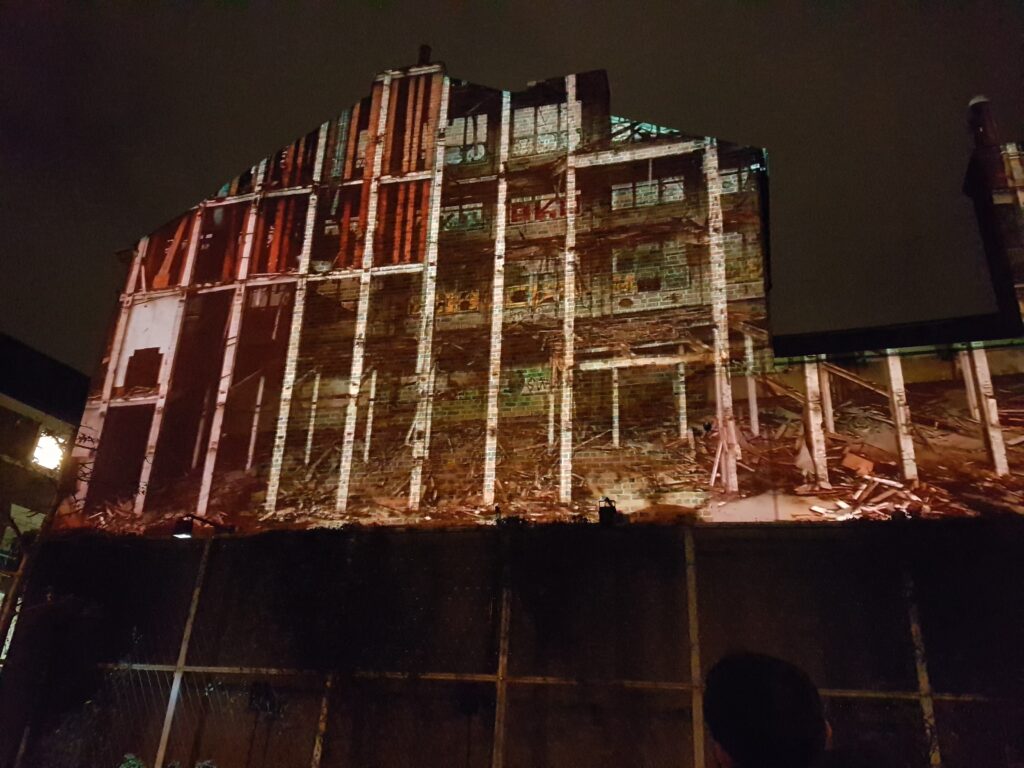

Dead Bod projected onto the Deep at the light launch of Hull City of Culture 2018

Following 40 years of neoliberal free market economics, Hull launched its campaign to become the UK City of Culture. This national award was inspired following Liverpool’s year as Europe’s Capital of Culture in 2008, where the social and economic benefits of holding this title saw an extra £800m spent in the city. Hull’s bid was launched by the release of a short film produced by Hull City Council, in which it showcased the unique character of the city so that it might win the title over its shortlisted competitor cities. In between various shots of the city and its surrounding landscapes, landmarks, and statues, a verse proclaimed “The Golden Rules of Hull”:

Don’t pretend you’re something you’re not, Don’t go thinking that you are better than anybody else, or that anybody else is better than you, Don’t shout about it, get on with it, We are Hull, Hull, Hull, Hull We’ve found our voice again, And rules are meant to be broken, because that’s how things get done.

As chair of the 2017 City of Culture panel, TV producer Phil Redmond pronounced Hull to be the unanimous winner due to its “most compelling case based on its theme as a city coming out of the shadows…. its cultural past and future potential.”

In this down-to-earth place years later, we still find ourselves amidst growing inequality, measured any which way you want. Here life’s expectations and aspirations are shaped in the mind’s eye of community, where young people are socialised in the sepia-toned decay of forever failing national policy. Here in Orchard Park and Bransholme cul-de-sacs, dreams of a brighter future are kept in check by economic grim reality and dry northern salt-of-the-earth wit. “Don’t pretend you’re something you’re not and don’t go thinking that you are better than anybody else, or that anybody else is better than you.” Life preparation for never being disappointed.

Future potential clutched from the loose change of a dismal present, optimism is reserved for the young who grow up too fast in utilitarian housing estates. The thin line of grey sky between rooftops acts as a metaphor for the lack of future horizon sun. In this damp, earth-grounded universe, young people adapt to survive in Bourdieu’s habitus. Monotone drizzle food bank queues, bread cake butties, and chip spice supper. Help for Heroes. Everybody else tolerates this. From Philip Larkin’s dusty old library books, ambition hides in the cobweb shade; out of sight from midsummer swift migration, birds of a feather don’t imagine a world beyond Here.

Pushed together by poverty, the poorest children live on top of each other where the occasional gap in the clouds hints at seasons. Keeping it real is asserted through community ties; struggle and success are rooted in the social structure of postcode location. Self-perception is painted by the landscape, joining up the dots into knots that tie street, mates, and family together. Ways of life shared between school leavers and co-workers alike; factory floor freedom; the nicotine buzz of a cigarette break.

However accurate these observations might be, they miss a far greater truth hiding in plain sight. Just beneath the surface, amazing potential awaits to be shown the light. Hull has an amazing sense of community with a huge array of charity organisations, social enterprises, and individual and collective social change facilitators. Hull also has an amazing culture of social solidarity that is more than capable of inspiring egalitarian socioeconomic transformation, given half a chance.

Ghosts of the past. The projected image of an industrial ruin projected as art.

Much of the city has been rebuilt or is under regeneration now, especially since the huge success of the City of Culture in 2017, which attracted much-needed positive vibrations and some development cash. Across the other side of the river Hull where sharks, turtles, and penguins swim around The Deep, the Fruit Market sector has been redeveloped. Flats, bars, and arts venues now seek to inspire more meaningful contemporary ways of life. Drinkers chatter in these newly cheered-up reconstructed Victoriana streets. Postmodern brick façades reassert the ghosts of past times, before World War 2 bombs split time from the traditions of the past. Cool culture vultures, microbrewery beards, anarchist artists, the lads and lasses, wait here eager to greet the good times, should they roll into town. For how much longer must people just drink here, before realising their potential to transform this amazing town?

Chloe: I’m from Bransholme (East Hull), it’s not as bad as it used to be when growing up, changed now from being a kid. As a kid there were lots of drugs down round n’ that, used to be a big issue—not anymore. It’s still an issue but not as many, in the community we know where drug dealers live and addicts are.

Interviewer: How does that make you feel about the area?

Chloe: Don’t know, been in area whole life. I wanna get out of it, but others don’t ‘cos it’s home. I want to go to Leeds University to study a joint honours degree in English literature and sociology, wanna get into publishing, always liked reading and how it works.

Interviewer: What sort of family are you from?

Chloe: Both parents were 18 when they had me. Mum dropped out of college to have me, but Dad stayed in college and became a demolition man. I live with them both now.

Interviewer: Do you work outside of college?

Chloe: Yes, I work about 8 hours a week at McDonald’s. It helps to pay gas, electric and food. I’ve always wanted to go to university.

Interviewer: Why do you want to go to university in Leeds?

Chloe: I don’t want to say it……

Interviewer: It’s OK, you don’t have to say anything if you don’t want.

Chloe: I want to get out of Hull and going to university is a way of getting out.

Interviewer: Why do you feel nervous saying that?

Chloe: ‘cos I feel that I shouldn’t say that.

Interviewer: Why?

Chloe: All my friends are staying in Hull and they’d think I’m looking down on them, but I don’t feel like that. Most of my family have stayed in Hull, except for two Aunts. I want to get out.

Interviewer: Do you think that many people feel like that and want to leave the city?

Chloe: No, I think it’s more about staying with your family and community.

Interviewer: Is there a strong sense of community where you live?

Chloe: Yes, all neighbors get together and have barbeques. There is a strong sense of community that you have to be part of to fit in. If you go to the pub and you’re a regular you’ll be accepted, if you just go in once they will be hostile.

Interviewer: Why do you think that you need to leave Hull to achieve your aspirations?

Chloe: I guess that I feel if I stay in Hull I will feel restricted, if I leave Hull, there will be new opportunities and new lifestyles.

(Interview with an A-Level student)

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu developed the concept of cultural capital in the 1970s to explain how ruling class power is maintained and legitimised in a structurally unequal society. It offers a way to understand how advantage and disadvantage are culturally transmitted between generations and how this manifests through educational outcomes and materially rewarding career success.

According to research commissioned by the National Union of Teachers in 2015, entitled “Exam factories – The impact of accountability measures on children and young people”, schools have only a limited influence on the educational attainment of pupils where their lives outside school are the main influences.

Their research showed that schools are responsible for only a small proportion of the variance in attainment between pupils. It argued that it is therefore unreasonable to expect schools alone to close the gap. The research investigated the impact that ever-increasing pressure on schools and further education colleges to maximise their qualification output has on pupils and teachers. The report also found that universities and employers have become increasingly critical of the way that young people are not prepared for life, because children and young people are increasingly seeing the main purpose of education is to gain qualifications. If unpreparedness for life was not a damning enough criticism of the education system, the report also found that more and more children and young people are suffering from high levels of school-related anxiety, stress, disaffection, and mental health problems. This is attributed to increased pressure from tests and exams, which creates a culture in which there is an awareness at younger ages of their own ‘failure’.

According to the Cultural Learning Alliance (CLA), an organisation that ‘champions the right to arts and culture for every child’, there is a risk that Ofsted’s focus on cultural capital being linked to ‘the best that has been thought and said’ is troubling, in that it has the potential to be used to entrench notions of class structure as outlined by the initial use of the concept devised by Bourdieu.

Instead, the CLA believes that we should define cultural capital to celebrate and embrace the different backgrounds, heritage, language, and traditions of all the children living in this country. For the CLA, a narrow definition of cultural capital risks maintaining the unequal status quo, as some children and young people will gain the keys to advancement, and this will help to maintain ruling class cultural dominance of society.

For many young people of East Hull and its surrounding environs on the East Coast, a life of poverty and its effects on aspiration and self-fulfilment are confounded by the machinery of neoliberal education. The system offers the next generation a route out of poverty if they do as they are told. Education is being drilled into practising how to pass exams rather than being inspired to view the world with increased wonder and curiosity.

The reality of life outside of mark schemes and mock exams is marginalised as if it doesn’t matter. The types of food you eat, the location of your home, the wallpaper on the kitchen wall, your parents’ jobs, the places where you holiday, friendship groups, community, and sense of identity—all are rooted in structural differences that make a huge difference as to how life perspectives are shaped and reinforced. Social class identities are subcultural dimensions of life, where hierarchical positions relative to one another reassert intergenerational common sense. Socialisation into a sense of social location that sets the scene for the role played in life and a sense of self in relation to the people around you.

This habitat is life lived in the world of social structures that shapes how a person perceives their place in the world. In place, young people awaken to life in the broad sweep of their most formative horizon. For some, this skyline is filled with fluffy clouds, where faces, rabbits, bears, monsters, and castles appear. A world of infinite possibilities opens up imaginations that are projected from the heavens above onto a life of opportunities. The warm golden sun of childhood fades to a myriad of reds making way for the shimmering magic of each star-filled nocturnal sky, to illuminate intergalactic infinity. In more affluent places, the springtime of youth goes undisturbed by poverty, and the dawn chorus of birds transcendentally meditates each morning into existence, where the abundant natural world sets the scene for each fresh new day.

In places like East Hull, poverty traps the radiance of dawn. In the grounded universe of pay-cheque-to-pay-cheque living, lived experience is survival of the fittest. Imagination is confined to grey box estates of mind in places like Orchard Park, Bransholme and Greatfield. Hidden out of sight from the cliché of childhood’s fleeting moment, the rural joy of summer swift migration is pushed out of existence by poverty and the necessity of the hand-to-mouth existence and a cul-de-sac frame of mind.

For those who are most disadvantaged, the future horizon is a thin line of space above the buildings, where in between clouds, there is a hint of seasons. The dawn chorus is the sound of the number 12 bus and a police siren responding to a neighbourhood disturbance.